JavaScript Boss Statements

Very Useful Resource! I suggest you take a whirl at the Learn JavaScript Online App. It has tons of little exercises involving functions. You will learn about functions today.

So far we have learned about the JavaScript types system and about these data types.

- number: These are numbers with arithmetic

- boolean: This is

trueorfalse. - string: These are blobs of text.

- array: These are sequences of objects. We access the objects using the [] operator

- node: These are elements on a web page.

We have learned about operators. They come in these types.

- arithmetic operators: +, - and friends

- relational operators: <, <= and friends

- boolean operators, !, &&, and || (not, and or)

- assignment operators: =, +=, *=, etc

We have seen expressions, which are combinations of operators and data.

So far, we can only run programs that execute statements in seriatum. This is boring. Today we change that by introducing boss statements

Boss statements control the path of execution of a program. They allow you to do these things.

- Store a procedure you use again and again under a name.

- Skip or select code to run.

- Run a segment of code repeatedly until some condition fails, or run the code for each item in a collection (array).

Functions

You are already using these. Here are some examples.

Number()This converts a numeric string into a number.String()This turns any JavaScript object into its string representation.console.log()This will put a comma-separated list of items to the console. It's JS's print statement.

Here are two more useful examples.

parseInt()This converts a numeric string into an integer.parseFloat()This converts a numeric string into a floating-point number.

> parseInt("3243452")

3243452

> typeof parseInt("3243452")

"number"

> parseFloat("6.02e23")

6.02e+23

> parseInt("cows")

NaN

Making a Function

You can do either of these. I show both because you will see them in OPC.

function functionName(arg1, arg2, arg3, .... )

{

//code

}

functionName = function(arg1, arg2, arg3, .... )

{

//code

}

In either case, you should read the top line

as "to define the function functionName,"

Notice that this is a subordinating clause and not a complete sentence. This is the mark of being a boss statement.

There is a little terminology here.

functionis a language keyword indicating we are defining a function.functionNameis the name we are giving the function. It is, in reality, just another variable name. In JS, functions are objects.- The items inside the parentheses are called arguments. They can be any valid JavaScript expressions. Functions can have zero or more arguments.

- The curly braces contain the function's implementation. This consists of the code we want the function to execute.

Calling a function When we invoke a function we say we are calling it.

Some Examples

Here we are making a function square

that squares a number.

function square(x)

{

return x*x;

}

let a = 5;

console.log(`The square of ${a} is ${cube(a)}`);

Running this puts this to the console.

The square of 5 is 25

Can one function call another? Yes.

function square(x)

{

return x*x;

}

function cube(t)

{

return t*square(t);

}

a = 5;

console.log(`The cube of ${a} is ${cube(a)}`);

Let's step through the program's execution.

- The function

squaregets read into memory. - The function

cubegets read into memory. - The variable

astores the number 5. console.logstarts to do its job. It puts "the cube of 5 is " to the console.- Next,

console.logtries to evaluatecube(5). - The value 5 gets passed to the argument

tincube. - The code in

cubestarts executing. First, the expression being returned, 5*square(5) must be evaluated. cubeencounterssquare(5).The value 5 is passed tosquare'sx.squareevalatesx*xand sees it is 25.squarereturns the value 25. This triggers two things: the function's execution is over. And the value 25 goes back tocube's5*square(5)and becomes5*25, which evaluates to125cubenow returns, ending its execution and it tellsconsole.logthatcube(5)evaluates to 125.console.logfinishes putting its text to the screen and you seeThe cube of 5 is 125- The program's execution ends.

JavaScript functions are different from math functions.

They can lack an input and and output. Ouput only occurs when

you have a return statement.

function hello()

{

console.log("Hello!");

}

hello()

This function has the side effect of leaving text in the console. It accepts no input and has no return statement, so it has no output.

Las Vegas You have heard the cliché, "What happens in Las Vegas stays in Las Vegas." You notice we kept changing the names of variable arguments because we had used them. This is unnecessary.

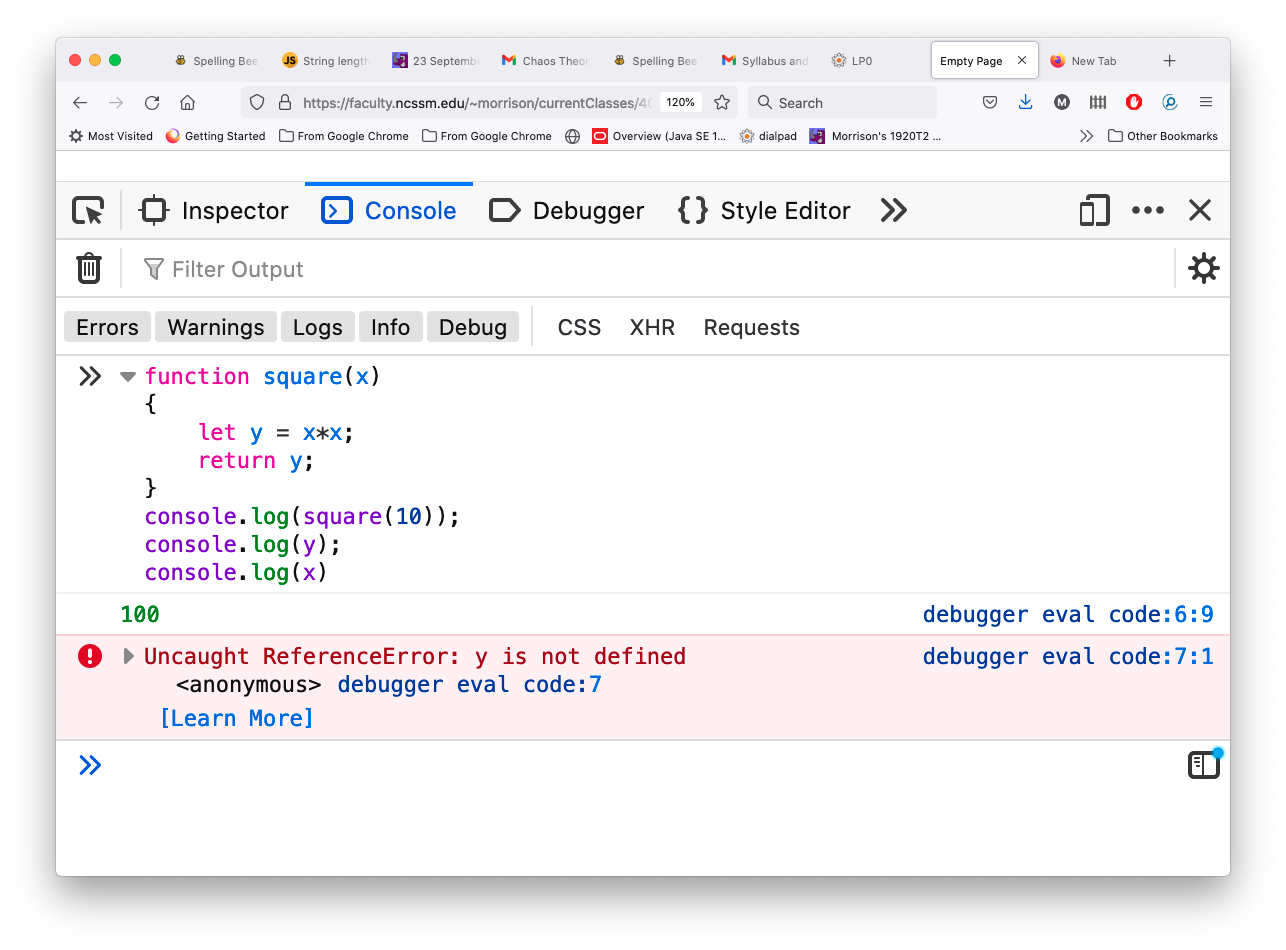

Let's run this program.

function square(x)

{

let y = x*x;

return y;

}

console.log(square(10));

console.log(y);

console.log(x)

Here is the result.

JS says, "I have never heard of y. Comment out the line that

prints y and JS will have a similar comment for x.

Here is the Las Vegas rule: Function parameters and variables are private to that function.

Warning!!! Use the let keyword to

create variables. Otherwise, this guarantee is vitiated and all manner

of chaos can ensue.

Do-Now Exercise Preconditions are what is guaranteed to be true when a function is called. Postconditions describe what is true once the function has executed.

/*

precondition: s is a nonempty string

postcondition: returns a string with the first and last characters of s

*/

function silly(s)

{

return s[0] + s[s.length - 1]

}

let x = "a"

console.log(silly(x) === "aa");

x = "lion"

console.log(silly(x) === "ln");

A little selection Notice that "if t < 0," is a subordinating class. It is a boss statement. It needs a block of code to complete it.

function foo(t)

{

if(t < 0)

{

t = -t;

}

return t;

}